Nov 16, 2021

COVID-19 Health Disparities to Be Aware of in Workers’ Comp

6 min read

Coverage of COVID-19 symptoms under workers’ compensation has been a heated topic.

Historically, illnesses like the flu or the common cold weren’t covered by workers’ comp insurance because no one could prove with certainty where they contracted a virus. However, the severeness and contagiousness of COVID-19 have made once safe jobs unsafe.

As many businesses required their employees to come in and face dangerous conditions, and even now, as companies are opening up everywhere, more people have begun to push for worker protection in the form of workers’ comp.

Now many states are enacting legislation to protect certain professionals in the event that they contract COVID-19 on duty, from first responders to grocery workers. You can see all up-to-date legislation by state, including who is covered, on the National Conference of State Legislatures website.

But as legislation requires workers’ comp professionals to work more often with COVID-19 patients, it is essential to be aware of the undue harm that the virus has wrought on minorities and what it means for their treatment and prevention in the workplace.

Health disparities among historically marginalized groups and the need for inclusivity aren’t new, but the recent pandemic has both highlighted the inequalities in health care and exacerbated the situation.

Shocking Numbers: Disparities in Hospitalizations and Deaths

Since the start of the pandemic, minorities have suffered higher rates of infection, hospitalization and even death compared to White people.

The Kaiser Family Foundation and the Epic Health Research Network conducted a study in which they analyzed the hospitalization and death rates per 10,000 Black, Hispanic, Asian and White patients. Their results yielded substantial discrepancies:

Hospitalization Rate / Death Rate Per Group

- Black patients: 24.6 / 5.6

- Hispanic patients: 30.4 / 5.6

- Asian patients: 15.9 / 4.3

- White patients: 7.4 / 2.3

In line with these other marginalized groups, CDC data shows that the death rate among American Indians and Alaska Natives is also more than double the death rate of White people.

Why These Inequalities Exist and Persist

A prominent cause of these inequalities is the social constructs that result in many minorities living within a lower socioeconomic status in the US. It’s why these individuals were disproportionately treated before and why COVID-19 compounded the problem.

Higher hospitalizations and deaths among minorities throughout the pandemic are due to several related factors tied to low socioeconomic status, including:

- Higher-risk jobs and lifestyles

- Greater comorbidities

- Difficulty accessing treatment

- Poorer health care provided

- Limited English proficiency and health literacy

As past US Surgeon General David Satcher, MD, PhD said in an interview:

“The pandemic has highlighted disparities in access to care…[It] has attacked the points of vulnerability in our society.”

Higher-Risk Jobs and Lifestyles

Minorities are more likely to work society’s unwanted jobs—jobs that are more dangerous or demanding. As a result, they are already more likely to injure themselves while working on construction sites, farms or in factories.

With the advent of COVID-19, these jobs became even more dangerous, as well as previously safe “lower class” jobs, like those in restaurants, transportation and grocery stores that require significant face-to-face contact with crowds of people.

Considered “essential workers,” these employees face a higher risk of exposure, and what you end up with is minorities heavily concentrated in industries where they can’t work remotely and are at risk of contracting COVID-19.

To make matters worse, more people from racial and ethnic minority groups live in crowded housing with more than one person to a room. This makes it harder to social distance and easier to spread the virus to family and roommates.

Those of a lower socioeconomic status are also more likely to use public transportation—where exposure to the virus is high—because they don’t have a vehicle of their own.

Greater Comorbidities

If high-risk jobs and lifestyles result in easier contraction of the virus, why are minorities also more likely to end up in the hospital or pass away?

One reason is another disparity that existed before COVID-19: there is a higher prevalence of comorbidities among minority groups. This is the case due to many of the same reasons discussed in this article.

In particular, hypertension, diabetes and obesity are higher among low-income, minority populations, and all three are tied to worse outcomes for COVID-19 patients.

Difficulty Accessing Treatment

To add to the higher rate of comorbidities, many low-income individuals have a hard time accessing medical treatment, whether due to poor knowledge of the healthcare system or being unable to afford it.

Overall, minorities are less likely to have health insurance, and immigrants, legal or otherwise, are often fearful of using the healthcare system.

As a result, those who do reach out to healthcare professionals often do so later than they should.

In addition to lack of insurance, having limited access to transportation, affordable child care or paid time off can make it difficult to see a doctor.

And even though their lower wages mean they can’t afford to take unpaid time off, it’s not uncommon for low-wage workers to lack paid sick leave. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of September 2021, two-thirds of low-wage workers still lack access to paid sick days.

Poorer Health Care Provided

Unfortunately, for those who do seek the treatment they need, the level of care received is also disproportionate. This is the case for two reasons:

- A lack of available resources in poorer areas

- Unjust biases towards racial and ethnic groups

In regards to the first, for instance, studies show that patients admitted to a hospital with less than 50 ICU beds are more likely to die. Additionally, research shows that 49% (almost half) of low-income communities don’t have any ICU beds, whereas this is only the case for 3% of high-income communities.

In respect to the second, racial biases or misperceptions result in worse care, treatment and counseling regarding patient options—all of which can influence health outcomes.

Limited English Proficiency and Health Literacy

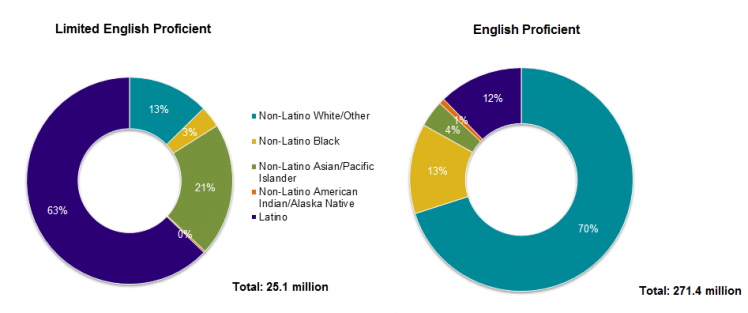

Two other causes of poor health outcomes for minorities in the US are Limited English Proficiency (LEP) and health literacy. According to the 2013 US Census Bureau, the majority of LEP speakers are minorities, and about half of all immigrants are LEP.

Difficulty understanding and speaking English, combined with poor information dissemination to more impoverished communities, results in lower health literacy among minorities.

In support of this concept, one study found that African Americans were less likely than White people to know the symptoms of COVID-19 and how it’s spread. They also left their homes more often.

Still, language barriers don’t just impact LEP speakers’ knowledge; they also result in inaccurate reporting of minority populations that is detrimental to the public’s knowledge of these populations.

Professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Robert Blendon explains that it’s expensive to conduct surveys in other languages to reach minority populations, especially Asian American populations that speak several languages. This means that surveys and polls often only reach the wealthier individuals within these racial and ethnic groups.

When there is inaccurate reporting and data, governments and policymakers can’t provide the help that is needed.

Addressing Disparities as a Workers’ Compensation Professional

Many of the individuals struggling to get the treatment they need are employees at a company.

As COVID-19 is increasingly covered under workers’ compensation insurance, it’s crucial that workers’ comp professionals acknowledge and adjust to the needs of historically marginalized groups.

There are a few ways you can start to reduce these disparities and save lives, both in your handling of minorities’ cases and the recommendations you give to employers.

One way to make a big difference is to remove health literacy barriers. Ensure that your clients share safety information with their employees and promote safe practices. Make a point of recommending the CDC’s safety guidelines and resources for the workplace to help prevent the spread of the virus.

When working with employees who have been exposed to the virus, make sure they understand how to get the care they need, take care of themselves and quarantine. Address common fears of the healthcare system with minorities and immigrants.

We also highly recommend hiring a language service that can help with interpretation and translation as needed to overcome language barriers among LEP patients.

In all of these ways, you can make healthcare more accessible.

To go the extra mile, you might consider screening injured employees for social needs, including housing, food and legal assistance. This allows you to connect them to existing local resources for low-income individuals in need. These resources make healthier outcomes more likely, especially if they enable the patient to take the necessary time off to heal or attend an appointment.

Along with the immediate symptoms of COVID-19, there is additional stress that comes with quarantining from work and more evidence coming out all the time regarding long-COVID (a variety of symptoms that may last for weeks after the initial symptoms have passed). These are also important to keep in mind when handling COVID-19 cases.

Increasing your awareness of the disparities in the healthcare system is the first step to making a difference. Acting on this awareness is the next.

By sharing this knowledge and following these tips, you can help to create a more just and equal workers’ compensation system.